TL;DR: In RLHF, there’s tension between the reward learning phase, which uses human preference in the form of comparisons, and the RL fine-tuning phase, which optimizes a single, non-comparative reward. What if we performed RL in a comparative way?

Figure 1:

This diagram illustrates the difference between reinforcement learning from absolute feedback and relative feedback. By incorporating a new component – pairwise policy gradient, we can unify the reward modeling stage and RL stage, enabling direct updates based on pairwise responses.

Large Language Models (LLMs) have powered increasingly capable virtual assistants, such as GPT-4, Claude-2, Bard and Bing Chat. These systems can respond to complex user queries, write code, and even produce poetry. The technique underlying these amazing virtual assistants is Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF). RLHF aims to align the model with human values and eliminate unintended behaviors, which can often arise due to the model being exposed to a large quantity of low-quality data during its pretraining phase.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), the dominant RL optimizer in this process, has been reported to exhibit instability and implementation complications. More importantly, there’s a persistent discrepancy in the RLHF process: despite the reward model being trained using comparisons between various responses, the RL fine-tuning stage works on individual responses without making any comparisons. This inconsistency can exacerbate issues, especially in the challenging language generation domain.

Given this backdrop, an intriguing question arises: Is it possible to design an RL algorithm that learns in a comparative manner? To explore this, we introduce Pairwise Proximal Policy Optimization (P3O), a method that harmonizes the training processes in both the reward learning stage and RL fine-tuning stage of RLHF, providing a satisfactory solution to this issue.

Background

Figure 2:

A description of the three stages of RLHF from an OpenAI blog post. Note that the third stage falls under Reinforcement Learning with Absolute Feedback as shown on the left side of Figure 1.

In traditional RL settings, the reward is specified manually by the designer or provided by a well-defined reward function, as in Atari games. However, to steer a model toward helpful and harmless responses, defining a good reward is not straightforward. RLHF addresses this problem by learning the reward function from human feedback, specifically in the form of comparisons, and then applying RL to optimize the learned reward function.

The RLHF pipeline is divided into several stages, detailed as follows:

Supervised Fine-Tuning Stage: The pre-trained model undergoes the maximum likelihood loss on a high quality dataset, where it learns to respond to human queries through mimicking.

Reward Modeling Stage: The SFT model is prompted with prompts \(x\) to produce pairs of answers \(y_1,y_2\sim \pi^{\text{SFT}}(y\vert x)\). These generated responses form a dataset. The response pairs are presented to human labellers who express a preference for one answer over the other, denoted as \(y_w \succ y_l\). A comparative loss is then used to train a reward model \(r_\phi\):

\[\mathcal{L}_R = \mathbb{E}_{(x,y_l,y_w)\sim\mathcal{D}}\log \sigma\left(r_\phi(y_w|x)-r_\phi(y_l|x)\right)\]

RL Fine-Tuning Stage: The SFT model serves as the initialization of this stage, and an RL algorithm optimizes the policy towards maximizing the reward while limiting the deviation from the initial policy. Formally, this is done through:

\[\max_{\pi_\theta}\mathbb{E}_{x\sim \mathcal{D}, y\sim \pi_\theta(\cdot\vert x)}\left[r_\phi(y\vert x)-\beta D_{\text{KL}}(\pi_\theta(\cdot\vert x)\Vert \pi^{\text{SFT}}(\cdot\vert x))\right]\]

An inherent challenge with this approach is the non-uniqueness of the reward. For instance, given a reward function \(r(y\vert x)\), a simple shift in the reward of the prompt to \(r(y\vert x)+\delta(x)\) creates another valid reward function. These two reward functions result in the same loss for any response pairs, but they differ significantly when optimized against with RL. In an extreme case, if the added noise causes the reward function to have a large range, an RL algorithm might be misled to increase the likelihood of responses with higher rewards, even though those rewards may not be meaningful. In other words, the policy might be disrupted by the reward scale information in the prompt \(x\), yet fails to learn the useful part – relative preference represented by the reward difference. To address this issue, our aim is to develop an RL algorithm that is invariant to reward translation.

Derivation of P3O

Our idea stems from the vanilla policy gradient (VPG). VPG is a widely adopted first-order RL optimizer, favored for its simplicity and ease of implementation. In a contextual bandit (CB) setting, the VPG is formulated as:

\[\nabla \mathcal{L}^{\text{VPG}} = \mathbb{E}_{y\sim\pi_{\theta}} r(y|x)\nabla\log\pi_{\theta}(y|x)\]

Through some algebraic manipulation, we can rewrite the policy gradient in a comparative form that involves two responses of the same prompt. We name it Pairwise Policy Gradient:

\[\mathbb{E}_{y_1,y_2\sim\pi_{\theta}}\left(r(y_1\vert x)-r(y_2\vert x)\right)\nabla\left(\log\frac{\pi_\theta(y_1\vert x)}{\pi_\theta(y_2\vert x)}\right)/2\]

Unlike VPG, which directly relies on the absolute magnitude of the reward, PPG uses the reward difference. This enables us to bypass the aforementioned issue of reward translation. To further boost performance, we incorporate a replay buffer using Importance Sampling and avoid large gradient updates via Clipping.

Importance sampling: We sample a batch of responses from the replay buffer which consist of responses generated from \(\pi_{\text{old}}\) and then compute the importance sampling ratio for each response pair. The gradient is the weighted sum of the gradients computed from each response pair.

Clipping: We clip the importance sampling ratio as well as the gradient update to penalize excessively large updates. This technique enables the algorithm to trade-off KL divergence and reward more efficiently.

There are two different ways to implement the clipping technique, distinguished by either separate or joint clipping. The resulting algorithm is referred to as Pairwise Proximal Policy Optimization (P3O), with the variants being V1 or V2 respectively. You can find more details in our original paper.

Evaluation

Figure 3:

KL-Reward frontier for TL;DR, both sequence-wise KL and reward are averaged over 200 test prompts and computed every 500 gradient steps. We find that a simple linear function fits the curve well. P3O has the best KL-Reward trade-off among the three.

We explore two different open-ended text generation tasks, summarization and question-answering. In summarization, we utilize the TL;DR dataset where the prompt \(x\) is a forum post from Reddit, and \(y\) is a corresponding summary. For question-answering, we use Anthropic Helpful and Harmless (HH), the prompt \(x\) is a human query from various topics, and the policy should learn to produce an engaging and helpful response \(y\).

We compare our algorithm P3O with several effective and representative approaches for LLM alignment. We start with the SFT policy trained by maximum likelihood. For RL algorithms, we consider the dominant approach PPO and the newly proposed DPO. DPO directly optimizes the policy towards the closed-form solution of the KL-constrained RL problem. Although it is proposed as an offline alignment method, we make it online with the help of a proxy reward function.

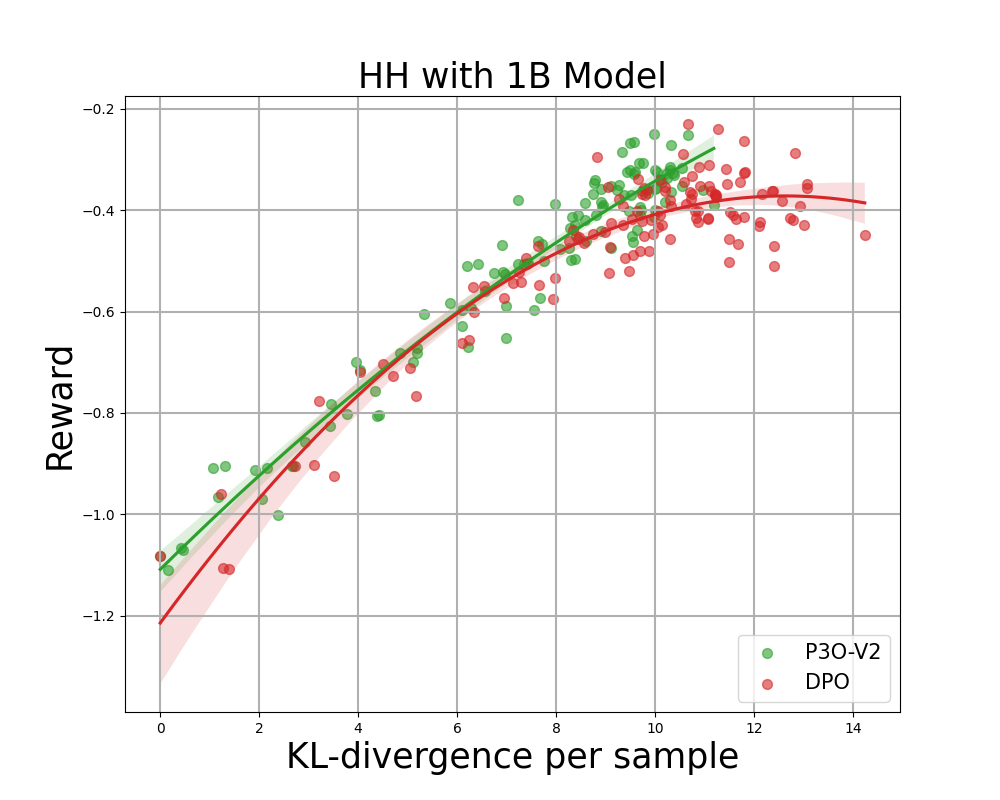

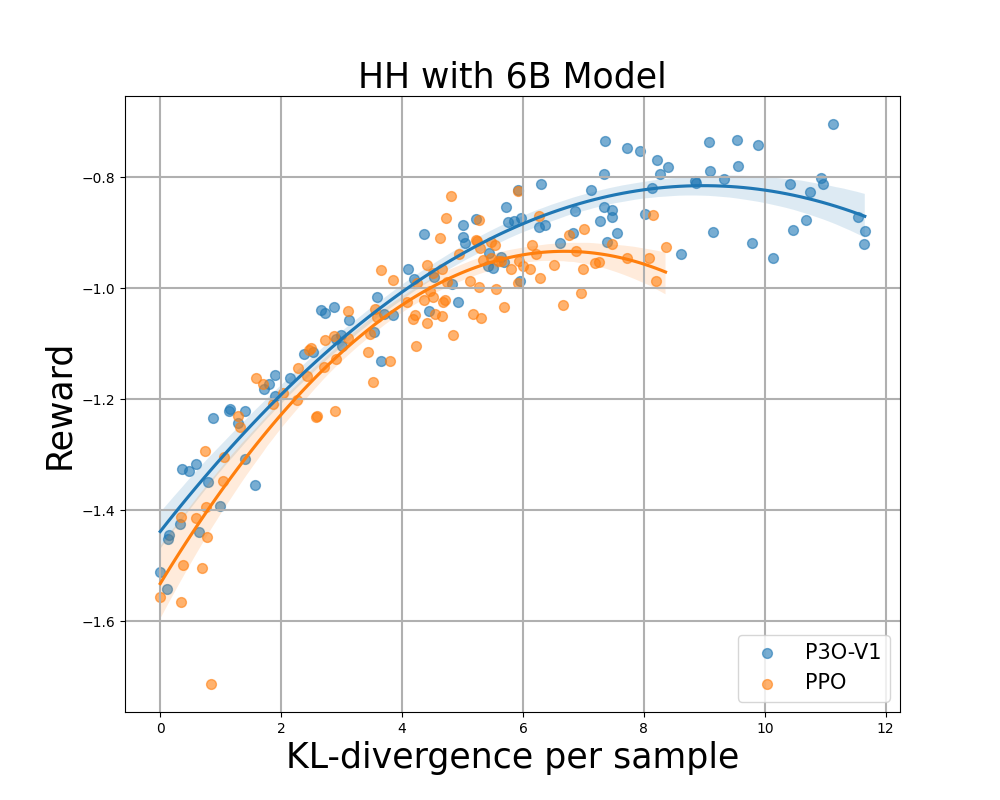

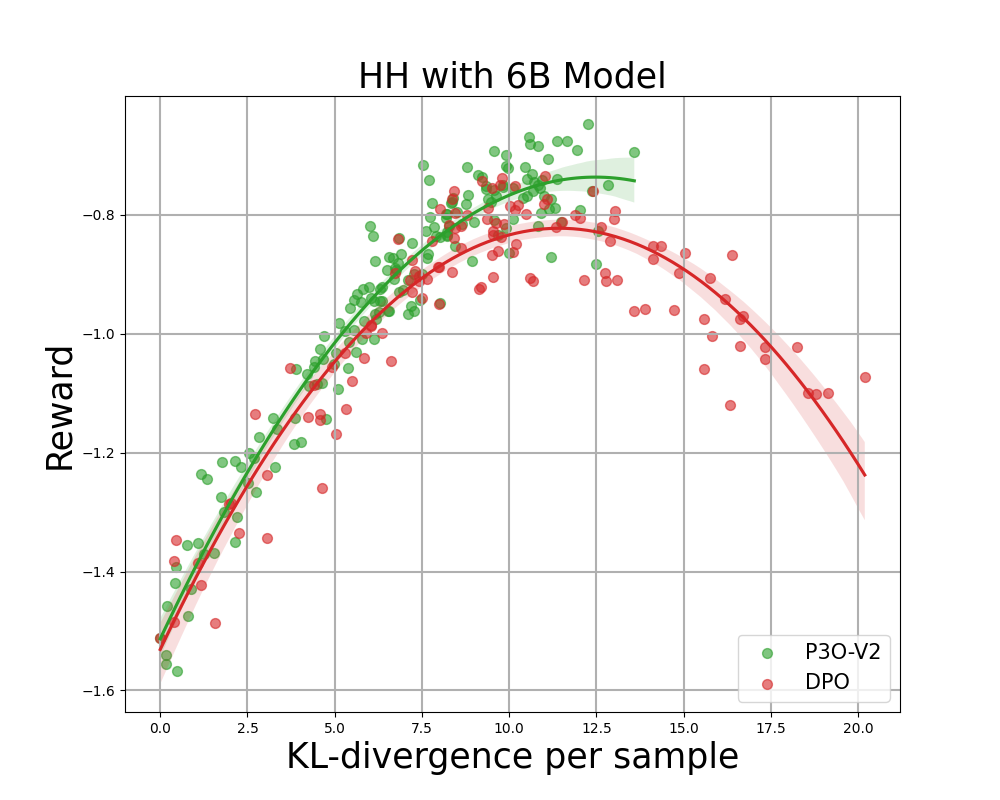

Figure 4:

KL-Reward frontier for HH, each point represents an average of results over 280 test prompts and calculated every 500 gradient updates. Left two figures compare P3O-V1 and PPO with varying base model sizes; Right two figures compare P3O-V2 and DPO. Results showing that P3O can not only achieve higher reward but also yield better KL control.

Deviating too much from the reference policy would lead the online policy to cut corners of the reward model and produce incoherent continuations, as pointed out by previous works. We are interested in not only the well established metric in RL literature – the reward, but also in how far the learned policy deviates from the initial policy, measured by KL-divergence. Therefore, we investigate the effectiveness of each algorithm by its frontier of achieved reward and KL-divergence from the reference policy (KL-Reward Frontier). In Figure 4 and Figure 5, we discover that P3O has strictly dominant frontiers than PPO and DPO across various model sizes.

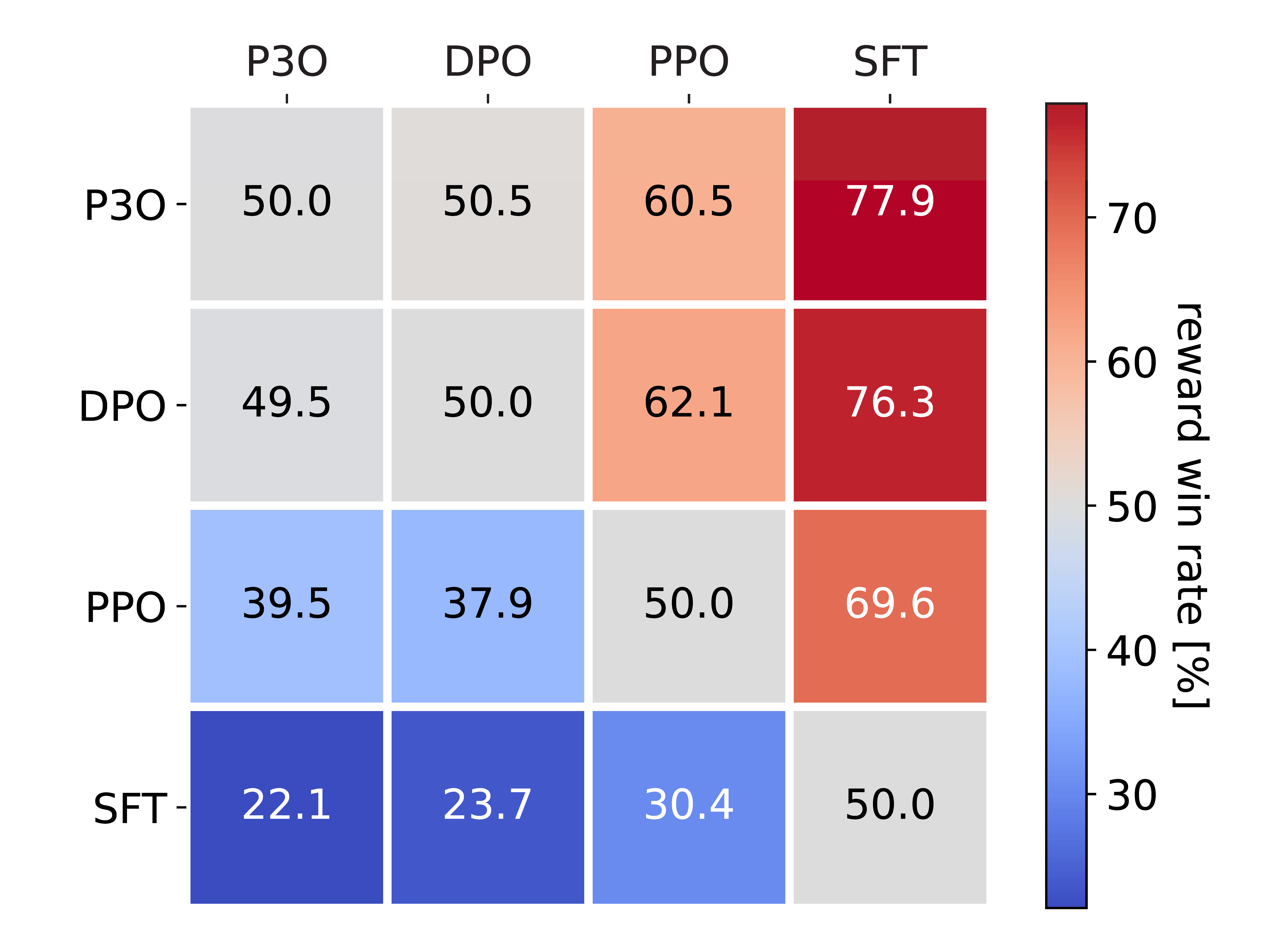

Figure 5:

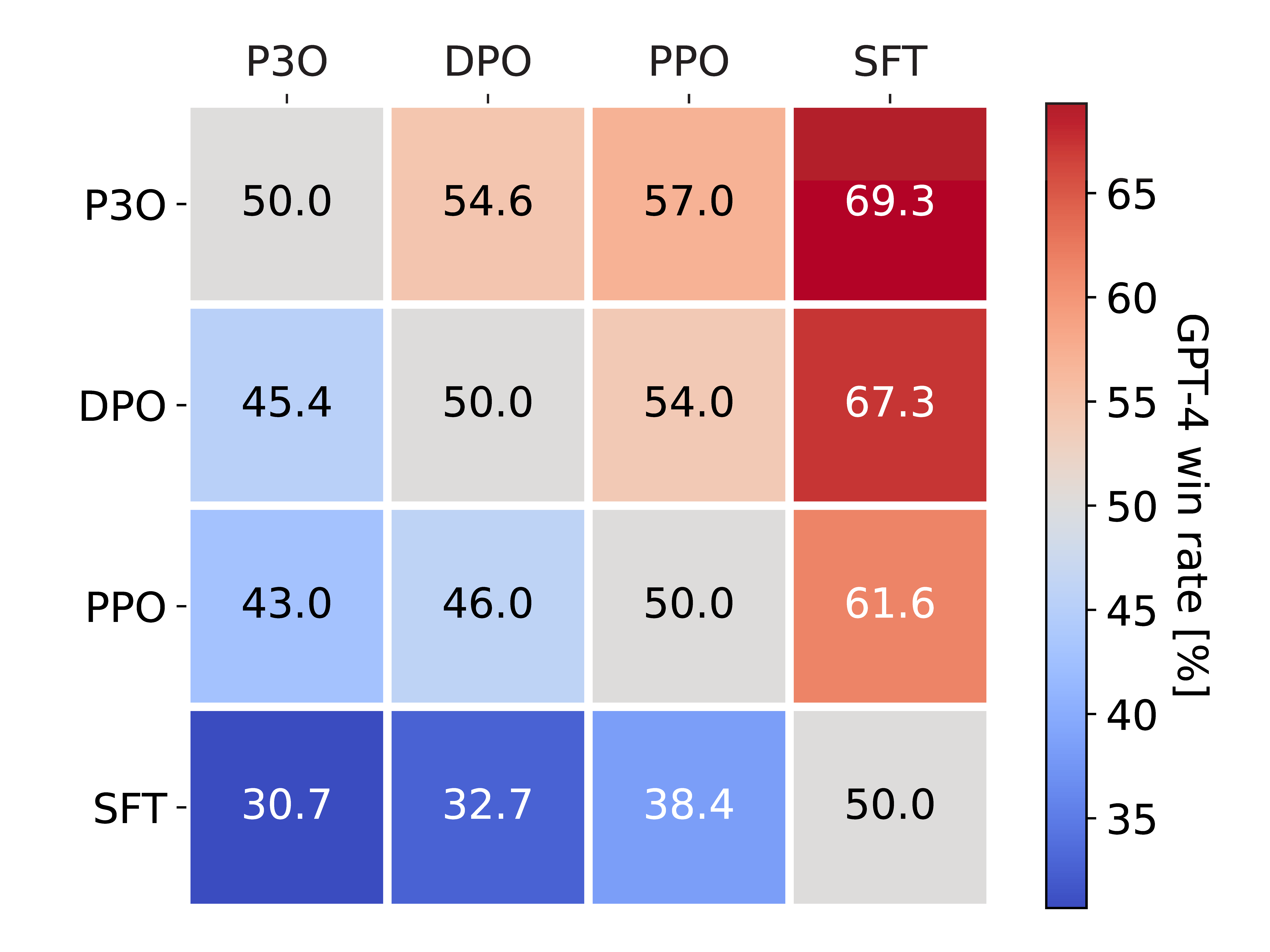

Left figure displays the win rate evaluated by GPT-4. Right figure presents the win rate based on direct comparison of the proxy reward. Despite the high correlation between two figures, we found that the reward win rate must be adjusted according to the KL in order to align with the GPT-4 win rate.

To directly assess the quality of generated responses, we also perform Head-to-Head Comparisons between every pair of algorithms in the HH dataset. We use two metrics for evaluation: (1) Reward, the optimized target during online RL, (2) GPT-4, as a faithful proxy for human evaluation of response helpfulness. For the latter metric, we point out that previous studies show that GPT-4 judgments correlate strongly with humans, with human agreement with GPT-4 typically similar or higher than inter-human annotator agreement.

Figure 5 presents the comprehensive pairwise comparison results. The average KL-divergence and reward ranking of these models is DPO > P3O > PPO > SFT. Although DPO marginally surpasses P3O in reward, it has a considerably higher KL-divergence, which may be detrimental to the quality of generation. As a result, DPO has a reward win rate of 49.5% against P3O, but only 45.4% as evaluated by GPT-4. Compared with other methods, P3O exhibits a GPT-4 win rate of 57.0% against PPO and 69.3% against SFT. This result is consistent with our findings from the KL-Reward frontier metric, affirming that P3O could better align with human preference than previous baselines.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we present new insights into aligning large language models with human preferences via reinforcement learning. We proposed the Reinforcement Learning with Relative Feedback framework, as depicted in Figure 1. Under this framework, we develop a novel policy gradient algorithm – P3O. This approach unifies the fundamental principles of reward modeling and RL fine-tuning through comparative training. Our results show that P3O surpasses prior methods in terms of the KL-Reward frontier as well as GPT-4 win-rate.

BibTex

This blog is based on our recent paper and blog. If this blog inspires your work, please consider citing it with:

@article{wu2023pairwise,

title={Pairwise Proximal Policy Optimization: Harnessing Relative Feedback for LLM Alignment},

author={Wu, Tianhao and Zhu, Banghua and Zhang, Ruoyu and Wen, Zhaojin and Ramchandran, Kannan and Jiao, Jiantao},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.00212},

year={2023}

}