I don’t know about you, but the highlight of my day is completing mind-numbing and repetitive tasks—manual data entry, downloading hundreds of images one-by-one, and searching every file on my desktop for the right document.

Can’t relate? Weird. But lucky for you, we live in a time where computers can help with the busywork we’ve become so accustomed to doing by hand. Python is a particular favorite programming language among those new to task automation.

I consulted with a Python expert to develop nine Python automation scripts, each of which can automate tasks you’ve been doing manually for way too long.

Table of contents:

Why automate tasks with Python?

Automation lets you hand off business-critical tasks to the robots, so you can focus on the most important items on your to-do list—the ones that require active thought and engagement.

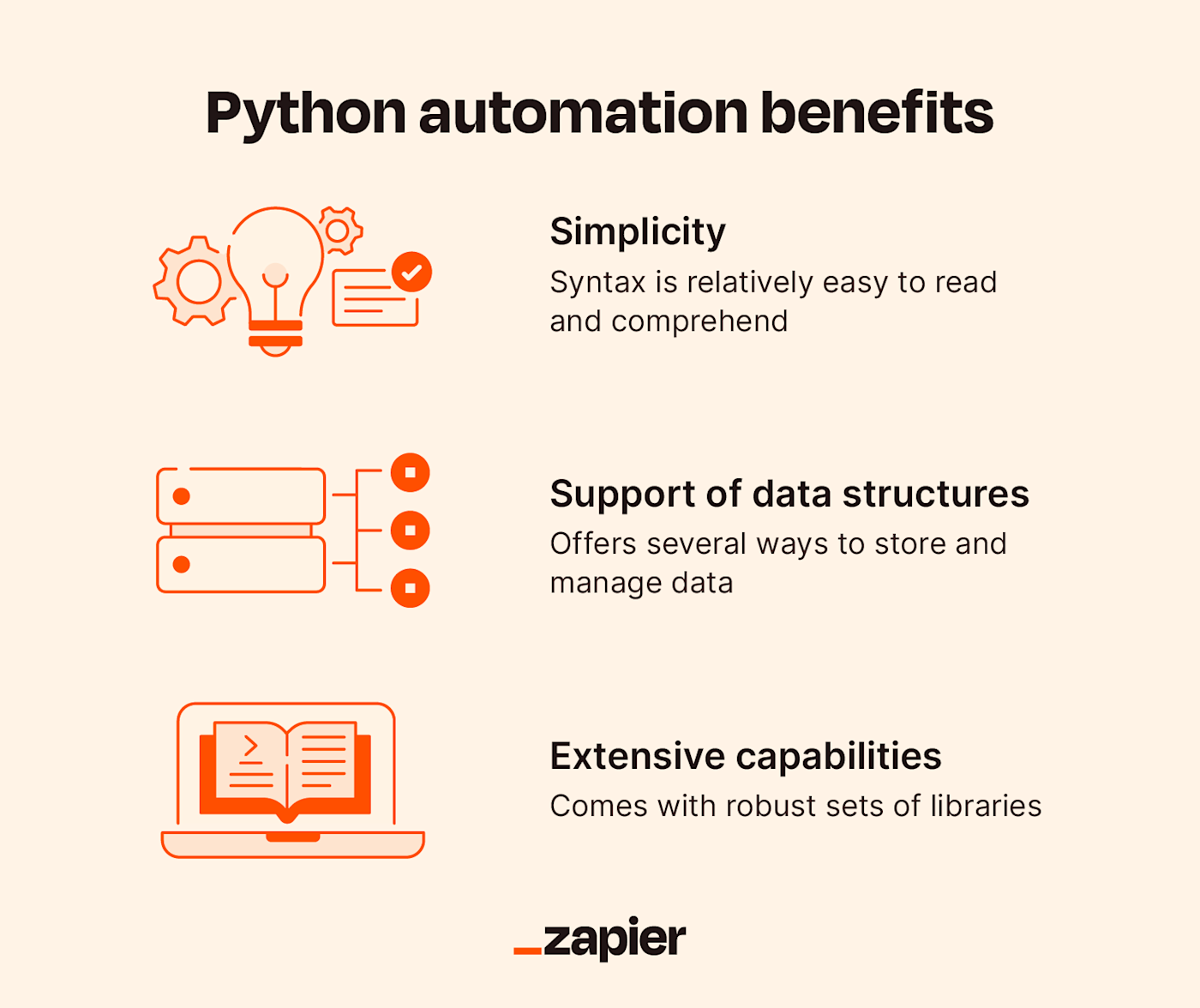

No-code automation should be your first stop, but Python’s popularity for task automation comes from a variety of factors, including its:

-

Simplicity and intuitiveness: Compared to many other programming languages, Python is very easy to read and comprehend. While learning a language like C++ or Java can feel like learning a foreign language, Python syntax resembles English.

-

Support of data structures: Python offers several ways to store data—including lists and dictionaries—and the ability to create your own data structures. This makes data management easy, improving automation responsiveness.

-

Extensive automation capabilities: Python comes equipped with a huge set of libraries that enable you to accomplish nearly any automation goal that comes to mind—machine learning, operating system management, and more. Plus, Python’s support network is huge, so you should be able to find an answer to nearly any automation question online.

How to run a Python script

Before you start creating scripts, here’s a little refresher on how to use Python. First, download Python onto your device (for free!). Once you download it, you can create and run a script.

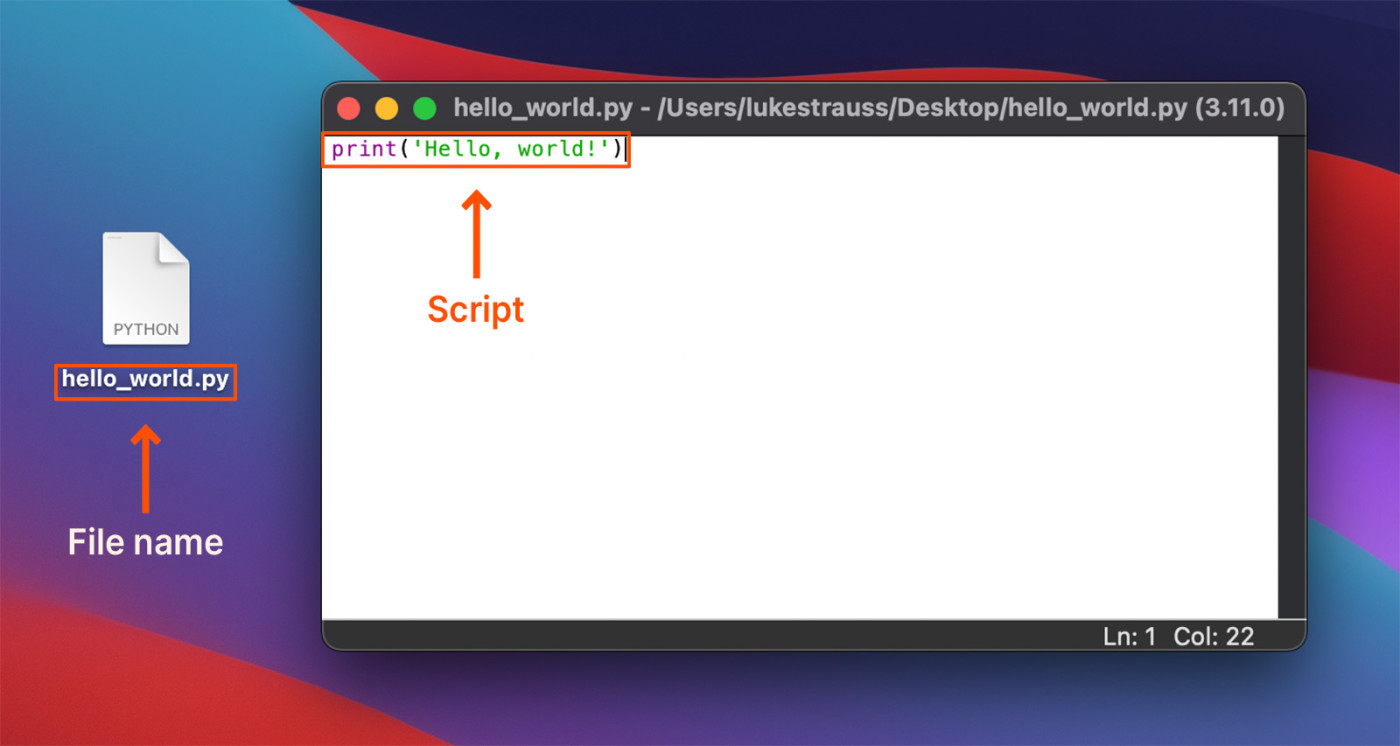

Your script file needs to be named with the extension .py, which stands for “Python.” This tells your device that the file will contain Python code. You’ll then add your script to this file and run it using your device’s command-line or terminal.

After creating your file and opening your terminal, type python3 followed by the path to your script. For example, on my Mac, I would:

-

Create an empty text file called

FILE.py. -

Add my script.

-

Open the Terminal app.

-

Type

python3. -

Drag the file into the app, and press enter, which would run the script.

I created a simple script as an example. Here’s what the file looks like:

And here’s what it looks like to execute the script in Terminal:

If you’re running one of the most recent versions of Windows, you should be able to type your .py file’s name in the Windows Command Prompt and run it without first typing the python3 command. And voilá—you’re ready to get automating.

9 useful Python automation script examples

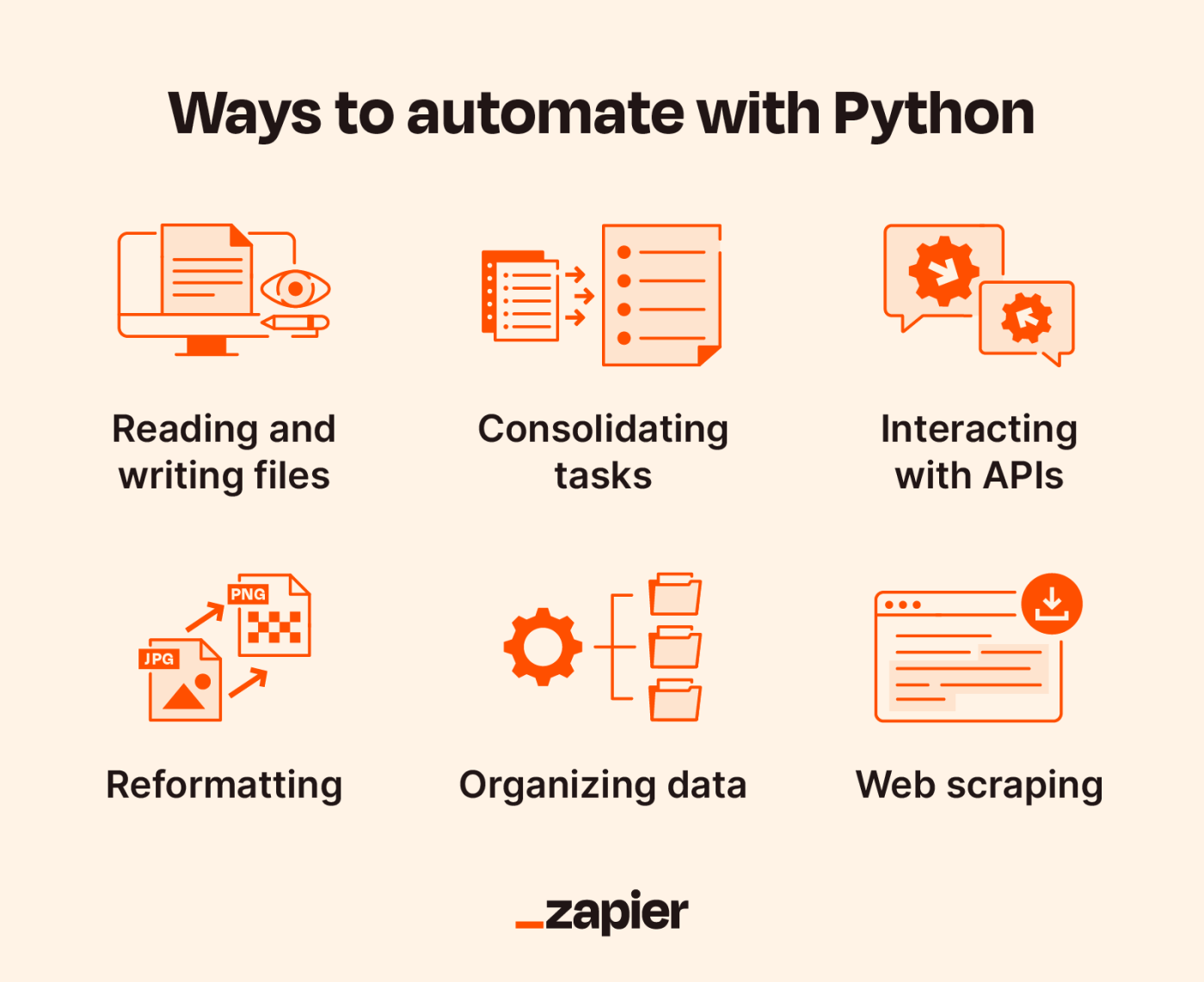

Uses of programming languages are practically unlimited, but nobody has time to learn every script there is. I’ve compiled nine Python automation ideas to simplify tasks that may otherwise distract you from important work, grouped into the following categories:

Running these scripts may require some preparatory steps, like downloading libraries. Follow the directions below, and you’ll have Python completing tasks for you in no time.

Retrieve real-time data using APIs

APIs make it possible to retrieve real-time data from third parties. Traffic data is always changing, so it presents a great opportunity to work with an API. With Python, we can quickly pull live traffic data as long as we have the URL where the API collects the data. For this example, I used TomTom’s API URL that enables access to live Los Angeles traffic data.

In the following script, I first install the requests library in order to gather data from the URL, then unpack the URL as a JSON file.

How it works

This script uses the popular requests library, which allows Python to communicate with external services over HTTP. Here’s a quick breakdown of what each part does:

-

Install requests: Before running the code, install the

requestslibrary by typingpip install requestsin your terminal. -

Request data from the API: The

get()object sends a request to the specified URL (the API endpoint). -

Parse JSON data: Once the response comes back,

json()converts it to a JSON object, which Python can easily process.

Example script: Pulling live traffic data

In the following script, I first install the requests library in order to gather data from the URL, then unpack the URL as a JSON file.

|

|

Once you have the data in JSON format, you can parse specific elements to create meaningful outputs. For example, you could extract the current traffic congestion level or save the data to a file for later analysis. Here’s an example of how you might use the JSON response:

|

|

Extract data with web scraping

If your workday involves regularly pulling fresh data from the same websites, Python’s web scraping capabilities can save you a lot of time. While it has specialized libraries to extract from specific sources like Wikipedia, the following script uses a more versatile web parsing and scraping library called Beautiful Soup.

How it works

Web scraping involves two key steps: downloading a webpage’s content and parsing the relevant data from it. In this example, we’ll use:

-

Requests library: To fetch the HTML content of a webpage

-

Beautiful Soup library: To parse the HTML and extract specific elements, such as headlines, product prices, or images

This method allows you to retrieve only the data you need, eliminating the clutter of extraneous content. Here’s a quick breakdown of the rest of the process:

-

Fetch page content:

requests.get(URL)sends a request to the target website. This checks if the request is successful (status code 200) and retrieves the HTML content. -

Parse the HTML: Beautiful Soup converts the raw HTML into a structured format that’s easier to navigate.

-

Extract Specific Data: Use methods like

soup.find_all(tag)to target specific elements on the page, such as headlines or links. For our example, we’ll pull all of the H2 headings.

Example script: Extracting website headlines

Use this script to pull today’s headlines from the BBC News home page. But first, ensure you have the necessary libraries installed.

|

|

|

i

|

Play around with the Beautiful Soup library to pull whatever data you need from a webpage with the punch of a command.

Convert text to audio file

For the visually impaired (or for those of us who would rather listen to an audiobook than pick up a physical copy), Python offers libraries that make text-to-speech a breeze.

How it works

For this script, we’ll be pulling from two Python libraries:

-

PyPDF2: A library that can read text from PDFs; it’s versatile and handles multi-page documents effectively

-

Pyttsx3: A text-to-speech library that converts text into audio; it allows you to generate audio files with natural-sounding voices, which can be saved and replayed

Here’s a breakdown of the process:

-

Extract text: The

PyPDF2library reads each page in the PDF and extracts its text content. -

Text-to-speech conversion: Using

Pyttsx3, the script converts the extracted text into spoken audio. -

Save as audio file: The output audio is saved as an MP3 file, creating a standalone audio version of the PDF.

Example script: Reformatting a PDF to MP3

|

|

Reformat image file

Converting between image formats is a tedious manual task, especially when dealing with multiple files. Python can automate this process, making it quick and efficient to convert images between formats. This is particularly useful when you need to prepare multiple images for web upload, standardize image formats across a project, or convert user-submitted images to a consistent format.

How it works

This script uses the Pillow library, a popular Python imaging library. Here’s a quick overview:

-

Import required libraries: For handling file paths and extensions, use

os.ImagefromPLprovides tools for opening, manipulating, and saving images. -

Define a list of images:

images = ['test.jpg']contains the names of JPG files to be converted to PNG format. You can replace ‘test.jpg‘ with the file names you want to process. -

Extract file names:

os.path.splitext(infile)separates the file name intof(the name without extension) ande(the extension). A new file name is created by appending.pngtof(e.g.,test.png). -

Check for output duplication: Ensure the input file (infile) is not the same as the output file (

outfile). -

Open and convert the image: Image.open(infile) opens the JPG file for processing, while

image.save(outfile), 'PNG'saves the opened image as a PNG file with the new file name.

Example script: Converting a JPG to a PNG

First, install the Pillow library if you haven’t already:

Then, use the following script to convert your JPG images to PNG:

|

|

Extract data from a CSV

CSV (Comma Separated Values) is a common format for importing and exporting spreadsheets from programs like Excel. Python can read a CSV, meaning that it can copy and store its contents. Once Python reads the spreadsheet’s contents, you can pull from these contents and use them to complete other tasks. For example, you can use this script to import customer information into your CRM system, analyze sales trends, or even feed data into other applications.

How it works

This script uses Python’s built-in csv module, which makes it simple to read and manipulate CSV files. Here’s what each part of the script does:

-

Open the file: The

open()function opens the specified file (customers.csv) in read mode. -

Create a CSV reader: The

csv.readerobject processes the file’s contents and splits it into rows based on the specified delimiter (default is a comma). -

Iterate through rows: A loop goes through each row in the file and prints its contents, joining them with a comma for easy readability.

Example script: Reading a CSV

|

|

Modify data in a CSV

You can also modify an existing CSV file using Python’s write feature. This replaces the contents in a CSV file without needing to enter new data manually. Learn more about how to read and write CSV files using Python’s CSV library.

How it works

This script demonstrates how to add a new row of data to an existing CSV file using Python’s csv library. Here’s a breakdown:

-

Data preparation: The new row,

['James Smith', 'james@smith.com', 200000], is defined as a list of values. -

File handling: The

open()function opens thecustomers.csvfile in append mode ('a'), ensuring the new row is added without overwriting the file. If the file doesn’t exist, it will be created. -

Writing the data: The

csv.writer()object writes the new row to the file, with fields separated by commas and special characters properly quoted. -

Confirmation: After adding the row, a success message confirms the operation.

Example script: Adding rows to a CSV

|

|

|

|

If you need to modify existing data instead of just appending it, you can first read the file into memory, edit the data as needed, and then write it back to the file:

|

|

Send personalized emails to multiple people

Nobody likes sending 30+ nearly identical emails, one-by-one. If you work in a field that requires this—marketing, education, or management, to name a few—Python makes this significantly easier. Start by creating a new CSV and filling it with all of your recipients’ information, then run the script below.

How it works

This script uses Python’s built-in smtplib for sending emails via Gmail’s SMTP server and csv to read recipient information from a CSV file. Here’s what each part does:

-

SMTP (simple mail transfer protocol): Handles the email-sending process securely

-

CSV file: Stores recipient information (name, email, and any custom data like scores), allowing the script to personalize each message

-

Template message: Uses placeholders to dynamically insert personalized information for each recipient

From there, the script:

-

Reads recipient data from

customers.csv -

Logs into Gmail securely using an app password

-

Iterates through each row of the CSV to personalize and send an email

Each recipient will receive a unique email tailored with their information.

Example script: Sending bulk emails with Gmail

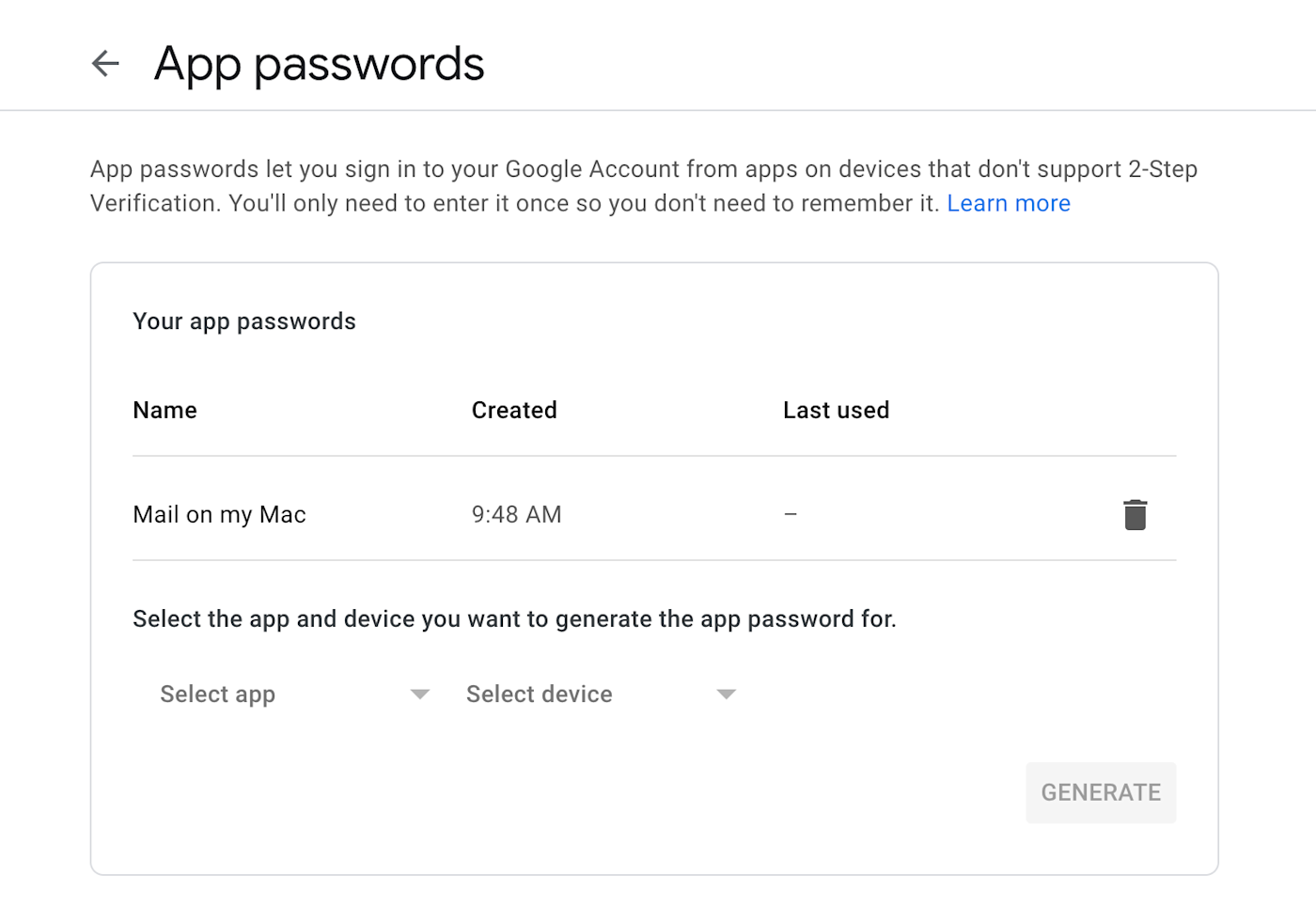

You may have to create an app password for Gmail to run the script. If you notice the script doesn’t run without one, create your password and enter it following the prompt Enter password: in the script.

|

|

Back up files to cloud storage

While uploading a single file to the cloud likely isn’t causing you a whole lot of grief, manually uploading tens or hundreds of files at a time can eat away at valuable time. Luckily, Python’s requests library (which we’ve pulled from in earlier scripts) can simplify this process.

How it works

This script uses the PyDrive library to interact with Google Drive. The process involves two main steps—authenticating with Google Drive and uploading files. Here’s a quick overview:

-

Google Drive API setup: You’ll need to create a project in the Google Cloud Console and enable the Google Drive API. This setup allows Python to interact with your Google Drive securely.

-

File uploading: The script iterates over a list of files in your local directory and uploads them to a specified folder in your Google Drive.

Example script: Bulk uploading to Google Drive

In order for Google’s authentication process to work, you’ll need to set up a project and credentials in your Google Cloud Dashboard. Here’s a quick overview of how to do this:

-

In an existing or new Google Cloud Project, navigate to Library > Search “Google Drive API,” and click Enable.

-

Navigate to Credentials > + Create Credentials > OAuth client ID

-

Create a consent screen by providing the required fields.

-

Repeat step two, this time selecting Application Type of Desktop App, and click Create.

-

Download the auth JSON file, and place it in the root of the project alongside the .py script below.

First, install the PyDrive library if you haven’t already:

Then, use the following script to upload your files:

|

|

Clean up your computer

If you’re like me and your computer desktop looks like a warzone, Python can help you organize your life in a matter of seconds.

How it works

We’ll be using Python’s os and shutil modules for this process, as they allow Python to make changes to your device’s operating system—think renaming files, creating folders, etc.—and organize files.

Here’s how this script works:

-

Create a destination folder: The script creates a folder named “Everything” (or appends a number to avoid overwriting an existing folder).

-

List desktop files: It identifies all files on the desktop, excluding the script file itself.

-

Move files: The script moves the files into the “Everything” folder, tidying up your desktop.

Example script: Cleaning up your desktop

We’re keeping it simple here, but feel free to play around with Python’s os and shutil modules to better organize your files.

|

|

Taking automation to the next level with Zapier

Zapier is equipped to automate a lot of processes—probably more than you know exist. But for those that aren’t directly built into Zapier, you can use Code by Zapier to create triggers and actions using JavaScript or Python.

It’s also very likely you can automate your workflows without any code at all. Zapier lets you automate your business-critical work with a visual builder—no code required.

Related reading:

This article was originally published in December 2022. The most recent update, with contributions from Allisa Boulette, was in December 2024.